Articles in recent newspapers, such as the Vancouver Sun, have unearthed a worrisome trend. While computer and general literacy levels are high in Canada (92.5 percent in British Columbia) in aboriginal communities they remain very low.

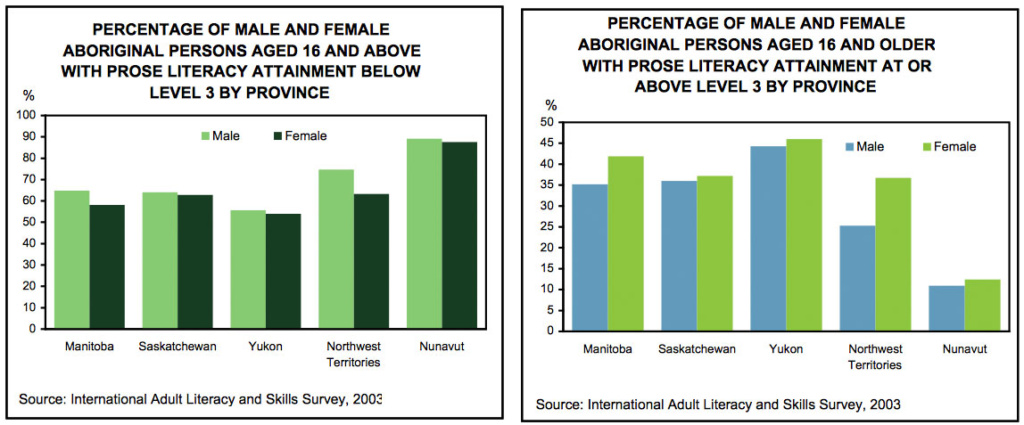

Nobody knows for sure the literacy levels of B.C.’s aboriginal population. Across the country, rates have only been measured in Manitoba and Saskatchewan. The results of that 2003 survey were alarming. About 72 per cent of urban Manitoban adult first nations scored below the benchmark level three literacy level, as did 70 per cent of first nations in urban Saskatchewan.

Those working on the ground say levels in B.C. are likely just as troubling, especially in the northern and central parts of the province. Estimates that up to 75 per cent of this region’s adult aboriginal population would need literacy upgrading before they could apply to a university.

Dropout rates for aboriginal students at central and northern high schools are extremely high, and those who stay in school often aren’t encouraged to take academic-stream classes. Aboriginals in the workforce, meanwhile, are still largely employed in the labour and resources sector, jobs with little opportunity to improve literacy skills.

But high school dropout rates and underemployment are often just the symptoms of deeper problems in aboriginal communities.

One major hurdle to improving literacy is the tainted relationship between aboriginal people and Western education due to colonialism and abuse.

But that is changing. There’s a growing movement to “indigenize” literacy education to make it relevant to aboriginal learners. The push to indigenize curricula through including more aboriginal and real world content is happening across the board.

At the preschool level, Aboriginal Head Start programs have a strong indigenous language and culture component. High schools across the province are offering a brand new course: English 12 First Peoples. Not only do students study literature and poetry by first nations writers, they look at creative expression beyond the pages of books, from oral stories to dance and film.